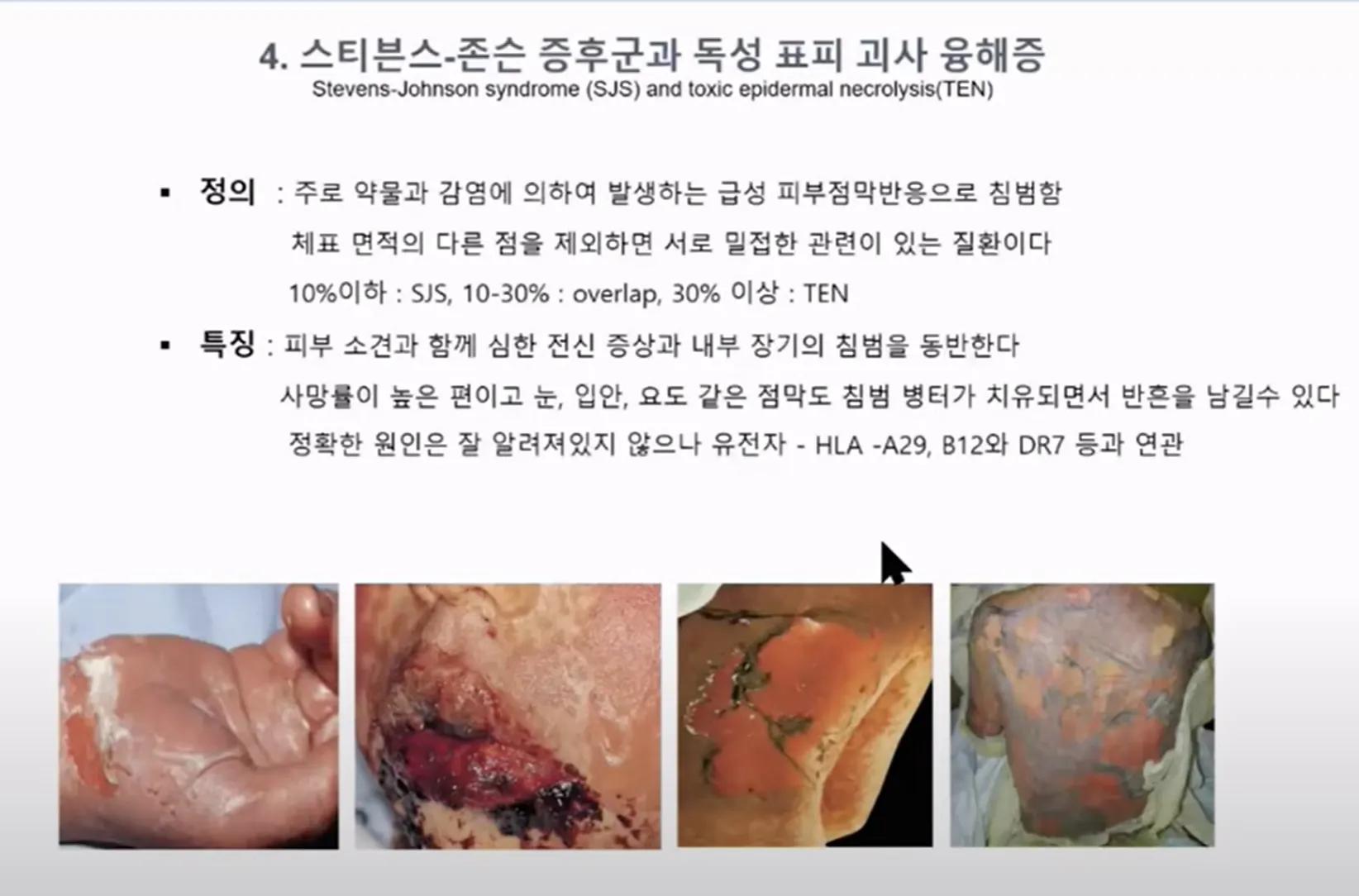

정의

스티븐 존슨 증후군은 피부병이 악화된 상태로 피부의 탈락을 유발하는 심각한 급성 피부 점막 전신 질환입니다

원인

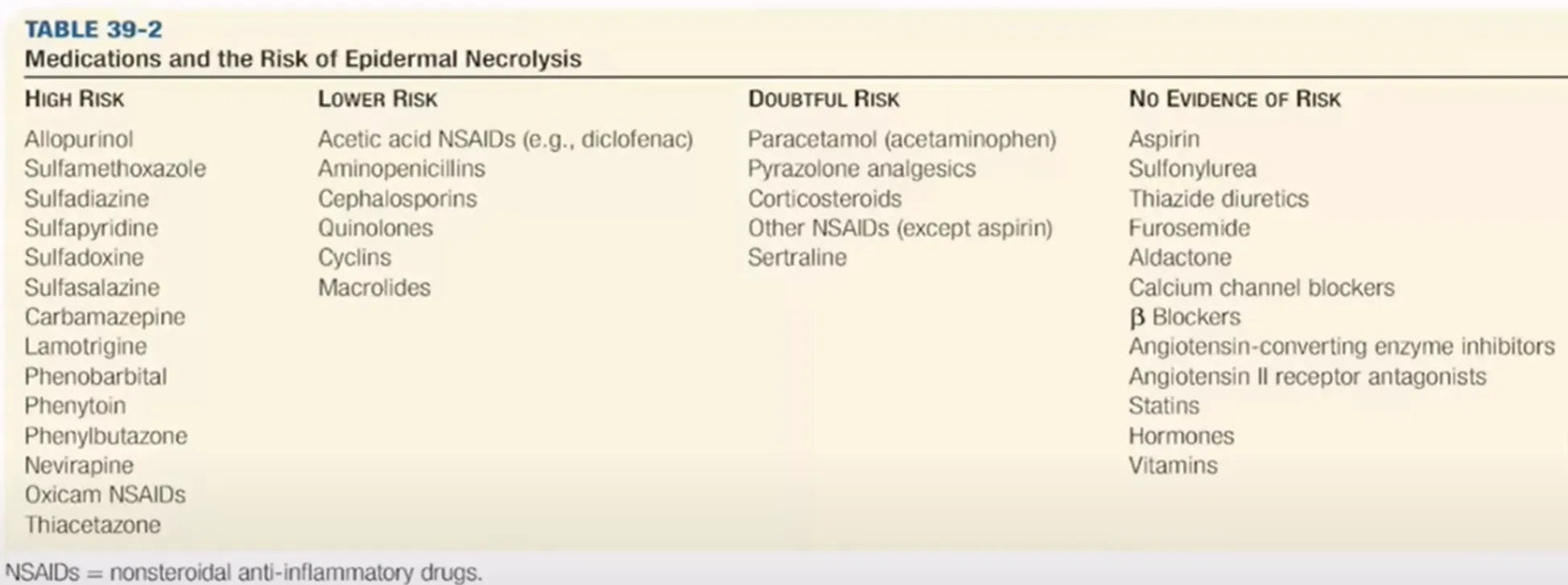

스티븐 존슨 증후군의 원인은 대부분 약물입니다.

현재 100가지가 넘는 약물이 보고됨. 대부분 항경련제, 페니실린계, 설파계 약물

스티븐 존슨 증후군의 50% 이상, 독성 표피 괴사 용해의 80~95%가 약물 때문에 발생합니다. 그 외에 결합 조직 질환, 악성 종양, 급성 이식편 대 숙주 질환, 예방접종, 폐렴 미코플라스마 감염증, 바이러스 질환 등에 의해 발생할 수 있습니다. 전체 환자의 5% 정도는 원인을 알 수 없이 특발성으로 나타납니다.

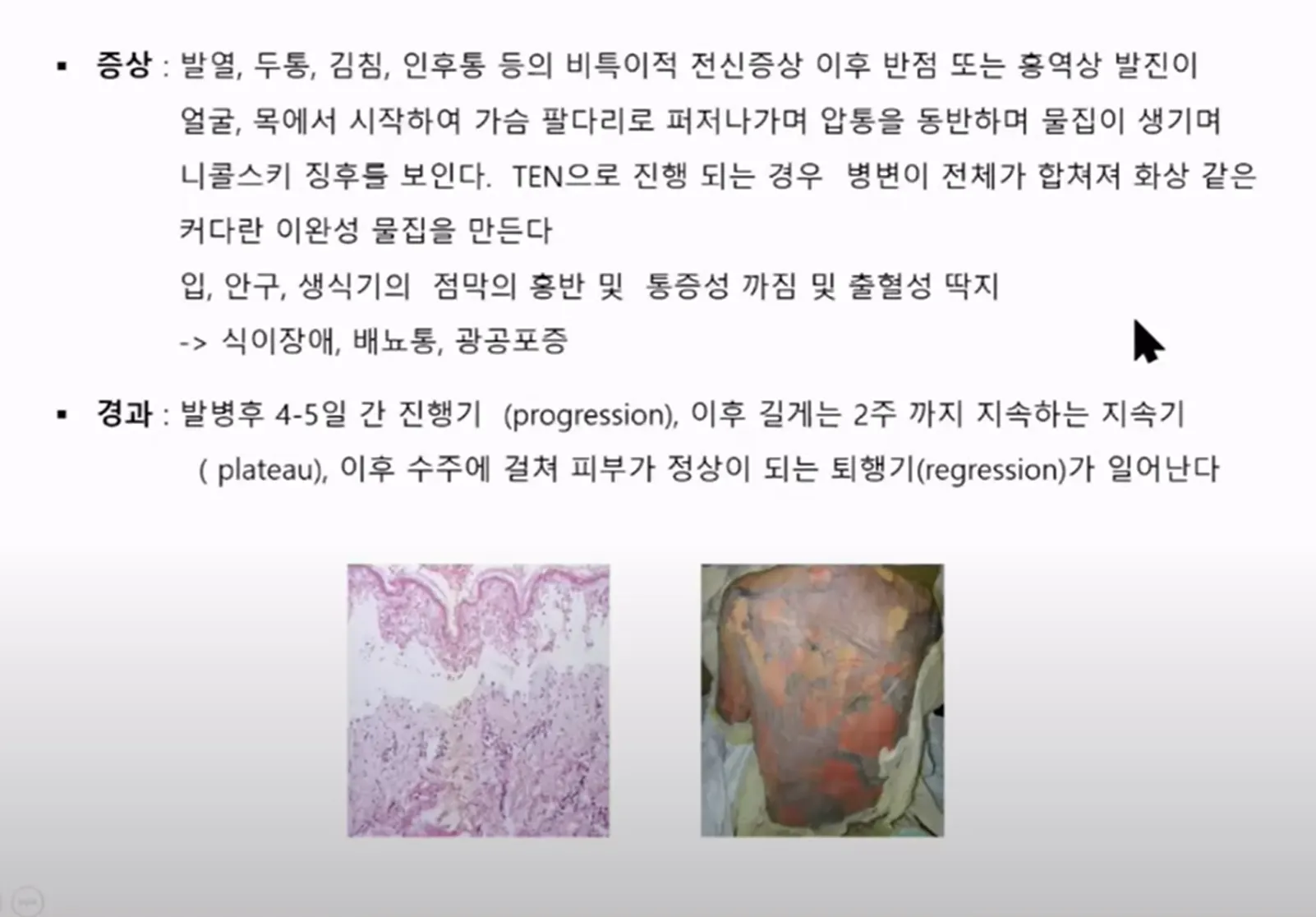

증상

스티븐 존슨 증후군의 특징적인 증상은 피부나 점액 막(점막 표피)의 염증입니다. 피부 병변은 대개 홍반성의 반점입니다. 반점은 융기되지 않은 표적 병터로 시작하여, 이것이 융합되면서 수포가 형성되고, 광범위한 피부 박리가 일어나며, 점막을 침범합니다. 심한 전신 증상이나 내부 장기의 침범을 동반하기도 합니다. 각 부위별 증상을 자세히 살펴보면 다음과 같습니다.

① 피부

피부 병변은 급격히 일어납니다. 대개 얼굴, 목, 턱, 흉부 등에 반점 혹은 홍역 모양 발진이 나타나기 시작하여, 사지 및 다른 신체 부위로 급격히 퍼져 나갑니다. 압통 및 니콜스키(Nikolski) 증후에서 양성을 보이기도 합니다. 때로는 출혈성 물집을 보입니다. 병변은 대개 4~5일경에 최대로 나타납니다. 체표면의 10~90% 정도에서 표피 박리가 진행되며, 독성 표피 괴사 용해가 심한 경우 조갑 및 모발 탈락도 나타날 수 있습니다.

② 점막

거의 모든 경우에서 병변이 구강과 입술까지 퍼집니다. 결막과 항문 외음부 점막도 침범됩니다. 전체 환자의 약 40%는 이들 세 곳에서 모두 증상을 보입니다. 작열감이 먼저 느껴지고, 물집이 터진 딱지나 궤양이 발생합니다. 입술은 출혈성 딱지로 덮입니다.

③ 눈

눈의 투명한 막(결막) 및 눈꺼풀의 감염, 결막의 염증(화농성 결막염)이 나타납니다.

•

결막붙음증 : 눈꺼풀과 안구가 유착된 상태입니다.

•

안구 건조증 또는 건성 각결막염 : 눈물샘이 막히거나 손상된 것으로, 안구 건조의 원인이 됩니다.

④ 기타

위와 장에 병변이 생기면 영양 부족이 나타날 수 있습니다. 호흡 기관의 병변으로 호흡 곤란, 배뇨 기관의 병변으로 배뇨 곤란이 나타날 수 있습니다.

진단

스티븐 존슨 증후군은 피부, 점막 등의 임상 증상을 토대로 환자의 약물 과거력을 통해 진단할 수 있습니다. 감별 진단을 위해 피부 조직 검사를 시행할 수 있습니다. 혈액 검사 등을 통하여 환자의 상태를 확인할 수 있습니다.

치료

스티븐 존슨 증후군은 생명을 위협하는 질환이므로, 즉각 원인 약제를 찾아내고 그 사용을 멈추어야 합니다.

환자의 약물 과거력을 살펴보았을 때, 원인 약물은 최근 4주 이내에 새로 투입된 약제이거나 위험도가 높다고 알려진 약물일 가능성이 큽니다.

스티븐 존슨 증후군의 치료는 환자의 상태에 따라 달라서 어렵고 복잡합니다. 그러나 초기에 질환이 진행되는 것을 막는 것이 중요합니다. 표피 박리가 심하면 화상과 거의 유사한 방법으로 치료합니다. 수분 및 전해질 균형, 이차 감염 치료, 괴사 조직 제거 등을 시도합니다. 급성기에 결막을 침범한 경우에는 유연제, 스테로이드, 항생제 등을 투여하는 안과적인 치료가 필요합니다.

스테로이드의 사용에 대해서는 논란이 많으므로 최대한 주의해서 투여해야 합니다. 병의 경과가 좋아지면 즉시 용량을 줄여야 합니다. 가장 심각한 사망 원인인 감염을 막기 위한 노력이 필요합니다. 호흡기 관리, 고칼로리 고단백 식이 등의 보조적인 치료도 중요합니다.

국소제 도포를 할 경우, 전신 흡수 가능성을 고려해야 합니다. 하이드로콜로이드나 거즈 드레싱 등을 이용한 국소 치료를 시행합니다. 실험적으로 사용되는 대체 치료법으로는 혈액 투석, 혈장 교환술, 사이클로스포린 등의 면역 억제제, 정맥 내 면역글로불린 주사 등이 있습니다.

경과

이 질환의 사망률은 정도에 따라 다릅니다. 스티븐 존슨 증후군의 경우 1%, 독성 표피 증후군의 경우 5~50% 정도입니다. 고령, 광범위한 병변, 호중구 감소증, 신기능 저하, 여러 약물 등은 예후를 나쁘게 하는 요인입니다.

1.1. Definition

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) comprise a continuum of a delayed hypersensitivity reaction affecting the skin and mucous membranes and is associated with a high risk of morbidity and mortality [[1], [2], [3]]. After an exposure to a causative agent, such as medications or pathogens, a viral-like prodrome progresses into the development of an erythematous, then blistering, and ultimately desquamating rash which can involve the skin; eyes; and mucosa of the mouth, pharynx, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, respiratory tract, and genitals [2,3]. SJS and TEN are distinguished by the total body surface area (TBSA) of skin involved. The former is defined by a TBSA of <10% while the latter is defined by a TBSA of >30%. TBSA involvement between 10 and 30% is designated as SJS/TEN overlap [2,3].

1.2. Epidemiology

SJS/TEN is rare. A study of inpatient records from 2009 to 2012 in the United States demonstrated an incidence of 9.2 per million adults per year for SJS, 1.6 per million adults per year for SJS/TEN overlap, and 1.9 per million adults per year for TEN; in children, the incidences are 5.3, 0.8, and 0.4 per million, respectively [4,5].

Risk factors for the development of SJS/TEN include certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes; variations in cytochrome p450 metabolism; a history of allergies to medications; and past medical history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection regardless of treatment status, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), connective tissue disorders, psoriasis, epilepsy, malignancy, cerebrovascular accident, and diabetes mellitus [[6], [7], [8]].

SJS/TEN carries a high risk of morbidity and mortality. The mortality rate of SJS is estimated to be 1–5% while the mortality rate of TEN is estimated to be 15–50% [6,[9], [10], [11], [12]]. Another study estimated the mortality of the SJS/TEN continuum at 23% at 6 weeks and 34% at one year [10]. Data suggest the mortality rate for pediatric patients with SJS, SJS/TEN overlap, and TEN is 0%, 4%, and 16%, respectively [5].

1.3. Pathophysiology

SJS/TEN is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction evoked by exposure to certain medications and, less commonly, to pathogens. There are a significant number of medications including allopurinol, anticonvulsants, antimicrobials, phenobarbital, and certain nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, as well as pathogens such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Herpes simplex virus (HSV), that are associated with SJS/TEN [2,8]. Although the microbiological intricacies of the disease process are yet to be fully elucidated, it is suspected that cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes and natural killer cells specific to the causative medication or infection release cytokines and chemokines which recruit other immune cells including neutrophils, monocytes, and eosinophils into the skin and mucosa, resulting in cellular necrosis [3,[13], [14], [15]]. With cessation of exposure to the instigating agent and meticulous supportive care, the affected areas will re-epithelialize [16].

2. Discussion

2.1. Presentation

SJS/TEN의 증상에는 급성기와 만성기가 포함됩니다. 징후와 증상은 원인 물질에 노출된 후 평균 3~4주 후에 발생하지만, 노출 후 빠르면 4일, 늦으면 8주 후에 증상이 나타난다는 보고도 있습니다[3,14]. 급성 진행기는 첫 증상 발생 후 7~9일 동안 지속되며, 이 기간 동안 환자는 전해질 이상, 탈수, 장기 손상(예: 신장, 간, 폐), 패혈증, 저체온증, 사망의 위험에 처할 수 있습니다[17,18]. 회복기 및 회복 단계가 있는 만성기는 질병 진행이 멈춘 다음 단계입니다.[19].

In addition to the cutaneous eruption, erosions of multiple mucous membranes are common, including the oral cavity, conjunctivae, genitals/urethra, nasal cavity, larynx, gastrointestinal tract, and bronchi [[22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]]. Of note, up to 80% of patients have involvement of two or more mucosal surfaces, and mucous membrane involvement can precede cutaneous lesions [18,29,30]. The absence of mucosal involvement should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses [3,31].

2.2. ED evaluation

Diagnosis of SJS/TEN is based on patient history and signs and symptoms. A careful review of any recent medication changes and infectious symptoms is paramount. The clinician must evaluate the skin, eyes, oral and nasal cavities, and genitourinary system to assess for the characteristic rash and mucosal erosions. Application of a gentle, lateral shearing force to erythematous, purpuric, or blistering areas should cause sloughing of the epidermis [3]. TBSA of the cutaneous lesions is calculated by including both detached and undetached areas of erythematous skin [14]. The skin examination should include assessment for superimposed cellulitis [3]. The eyes should be assessed with ultraviolet light and fluorescein staining [32]. An assessment of the airway and breathing is necessary due to the risk of mucosal lesions or superimposed pneumonia complicating the respiratory effort [1]. An assessment of volume status is also necessary due to the risk of volume depletion [3].

There is minimal role for laboratory and radiographic studies in the diagnosis of SJS/TEN in the ED. However, laboratory and radiologic studies are crucial in the assessment for superimposed infections and injury to the lungs, liver, and kidneys [1,3,33,34]. Therefore, it is reasonable for the emergency clinician to obtain a complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes and renal function, hepatic function panel, coagulation studies, lactic acid level, inflammatory markers, urinalysis with urine culture, blood cultures, and chest radiograph. HIV and Mycoplasma pneumoniae screening can be considered [3,33]. The diagnosis is aided through biopsy and histopathologic testing of lesions by specialists in dermatology and pathology, though the results will not be available in the ED setting. Suggestive histopathologic findings include apoptotic keratinocytes, full thickness epidermal necrosis, and infiltration of inflammatory cells into the dermis [3,35]. Histopathologic testing of perilesional skin can assist in ruling out autoimmune blistering conditions [3]. As in-person dermatologist consultation and histopathologic testing is not available in many EDs, the emergency clinician must heavily weigh the appearance of the mucocutaneous lesions and history of recent exposures to determine if SJS/TEN is likely.

2.3. ED management

As in the management of any patient presenting to the ED with a serious illness, the emergency clinician must first identify and stabilize immediate life threats due to complications involving the airway, breathing, and circulation and resuscitate if necessary. In patients with SJS/TEN, the relevant considerations include tenuous airways due to oral, pharyngeal, and respiratory mucosal injury and hypotension due to hypovolemia, infection, or both [36,37]. Sepsis must be considered in any patient presenting in critical condition or with abnormal vital signs, as it is the leading cause of death in patients with SJS/TEN [15]. 따라서 초기 응급실 치료에는 기도 관리, 균형 잡힌 결정체 주입을 통해 삼투압을 달성한 후 박리된 피부 조직과 소변 배출량의 TBSA에 따라 유지 결정체 주입을 시작하고 수액 소생술 후 지속되는 저혈압을 위해 혈관압박제를 시작하는 것이 포함될 수 있습니다. 감염이 의심되는 경우 광범위 항생제 치료를 시작해야 합니다. [2,3,16,28,37]. After resuscitation and stabilization of immediate life threats, the emergency clinician must identify and discontinue the offending agent, which significantly improves survival in patients with SJS/TEN [39]. Supportive care in the ED includes the administration of analgesics and anti-emetics, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, and the provision of wound care [3,32]. Patients with suspected SJS/TEN require admission at a hospital with expertise in burn care and dermatology, as well as broad specialist availability, which is associated with improved outcomes [14,32]. A의 효과에 대해 논란이 있는 경우, 사이클로스포린, 에타너셉트, 인플릭시맙 및/또는 IVIG와 같은 비경구 면역 조절 요법의 시작을 입원 담당 의사에게 연기해야 합니다. [33].

3. Pearls and pitfalls

3.1. What are the key risk factors for SJS/TEN?

The most important risk factor for SJS/TEN is recent initiation of a medication with known associations to the development of the disease (Table 1). There is evidence that higher doses of these medications, or decreased medication clearance, such as due to decreased renal function, increases the risk for the development of SJS/TEN [40]. Additionally, recent exposure to certain infectious agents, such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae and HSV increases the risk for the development of SJS/TEN, particularly in children [41]. However, up to 30% of cases have no identifiable trigger [42].

Acetic acid-type NSAIDs (e.g., diclofenac, indomethacin) | Nivolumab |

Allopurinol | Oxcarbazepine |

Abacavir | |

Atezolizumab | Pantoprazole |

Carbamazepine⁎ | Pembrolizumab |

Cephalosporin-type antibiotics | Penicillin-type antibiotics |

Durvalumab | Phenobarbital⁎ |

Fluoroquinolone-type antibiotics | Phenytoin⁎ |

Ipilimumab | Sertraline |

Lamotrigine⁎ | Sulfa-containing antimicrobials⁎ |

Macrolide-type antibiotics | Sulfasalazine⁎ |

Nevirapine⁎ | Tetracycline-type antibiotics |

⁎

Other risk factors associated with SJS/TEN include genetic predisposition because of HLA haplotype and cytochrome p450 metabolism, past medical history of HIV regardless of treatment status, SLE, connective tissue disorders, psoriasis, epilepsy, malignancy, cerebrovascular accident, diabetes mellitus, and allergies to other medications [8,15,40,43].

3.2. When should the emergency clinician consider SJS/TEN based on the history and examination, and what is the differential diagnosis?

In the ED, SJS/TEN must be suspected clinically when a patient presents with the characteristic, painful mucocutaneous eruption of erythematous or purpuric macules with progressive blistering and involvement of mucous membranes. Lack of mucous membrane involvement significantly decreases the likelihood of the diagnosis. Recent exposure to certain medications and infections supports the diagnosis of SJS/TEN; however, the absence of an identifiable trigger in the setting of a suggestive mucocutaneous eruption does not rule out the diagnosis. The Algorithm for Assessment of Drug Causality in Epidermal Necrolysis (ALDEN) is a useful tool to assist clinicians in the determination of causative medications (Table 2) [14]. However, due to the appearance of the skin findings and manifestations of SJS/TEN, there are a number of conditions that present in a similar manner (Table 3).

Criterion | Result | Value |

Delay from initial drug component intake to onset of reaction | From 5 to 28 days (If previous reaction to drug, from 1 to 4 days) | +3 |

From 29 to 56 days | +2 | |

From 1 to 4 days (If previous reaction to drug, from 5 to 56 days | +1 | |

>56 days | −1 | |

Drug started on or after index day of reaction | −3 | |

Drug present in the body on index day | Drug continued up to index day or stopped at a time point <5 times the elimination half-life before index day | 0 |

Drug stopped at a time point prior to the index day by more than five times the elimination half-life but liver or kidney function alterations or suspected drug interactions are present | −1 | |

Drug stopped at a time point prior to the index day by more than five times the elimination half-life, without liver or kidney function alterations or suspected drug interactions | −3 | |

Pre-challenge/re-challenge | SJS/TEN resulted after use of same drug | +4 |

SJS/TEN resulted after use of similar drug, or patient sustained a different reaction to the same drug | +2 | |

Non-SJS/TEN reaction after use of similar drug | +1 | |

No known previous exposure to drug | 0 | |

Patient exposed to drug without any reaction | −2 | |

De-challenge | Drug stopped | 0 |

Drug continued without harm | −2 | |

Type of drug / notoriety of drug to cause SJS/TEN | Drug considered high risk according to EuroSCAR study | +3 |

Drug with known association but not high risk according to EuroSCAR study | +2 | |

Several previous case reports, but ambiguous epidemiology results | +1 | |

Any drug not fitting the other categories | 0 | |

No evidence of association from previous epidemiology studies with sufficient number of exposed controls | −1 | |

Other cause | Rank all drugs from highest to lowest intermediate score. If at least one has an intermediate score >3, subtract 1 point from the score of each of the other drugs taken by the patient | −1 |

Score Interpretation:

<0: Very unlikely.

0 and 1: Unlikely.

2 and 3: Possible.

4 and 5: Probable.

>5: Very probable.

Table 3. SJS/TEN Differential Diagnosis.

Diagnosis | Classic Appearance |

Painful blisters on normal or erythematous skin with frequent mucosal involvement | |

Superficial cutaneous lesions similar to PV, but no mucosal involvement. | |

Akin to SJS/TEN, but cutaneous lesions occur in a photo distribution | |

Tense vesicles and/or bullae appear upon normal or erythematous skin, associated with mucosal erosions; can be drug-induced | |

Painful, erythematous cutaneous patches with blister formation, sparing mucous membranes, progressing over the course of hours; young children most commonly affected | |

Pruritic or tender maculopapular eruption within 100 days of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant; can be associated with oral lesions, abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract and liver | |

Centripetally spreading erythematous papules which develop target-like appearance and can be associated with mucosal erythema, erosions, or ulcers | |

Maculopapular eruption and/or coalescing erythema often involving >50% TBSA, mild mucosal involvement, no desquamation; often associated with fever, lymphadenopathy, visceral and hematologic abnormalities; occurs 2–8 weeks after exposure to a medication | |

Numerous non-infectious pustules on erythematous and/or edematous skin within hours to days of administration of a medication; 25% have mucosal involvement, but >1 mucous membrane is uncommon | |

Maculopapular reaction within 1–2 weeks of new medication exposure, without mucosal involvement | |

Round, hyperpigmented macule(s) with or without blistering and can involve mucous membranes within 2 weeks of medication exposure; rarely, can present as generalized reaction |

3.3. What is the Nikolsky sign?

The Nikolsky sign is a physical examination finding which describes the separation of epidermal cells from each other when a gentle, lateral shearing force is applied to an area of skin. The Nikolsky sign can be present over existing lesions, in the perilesional skin, and even in areas of normal-appearing skin distant from the active lesions. It is a manifestation of acantholysis, which is the loss of connection between epidermal cells at the desmosomes. When the Nikolsky sign is present, the differential diagnosis includes pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS). In these diseases, the desmoglein proteins which comprise the desmosomes are targeted by autoantibodies or infectious exfoliative toxins, resulting in sloughing when lateral shearing force is applied [[59], [60], [61], [62], [63]].

The Nikolsky sign is distinguished from the pseudo-Nikolsky sign, which is present in SJS/TEN, thermal burns, and bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma. The pseudo-Nikolsky sign is present when a gentle, lateral shearing force is applied to an erythematous or purpuric area and results in epidermal sloughing. Skin with normal appearance should not slough. The pathophysiology of the pseudo-Nikolsky sign is cellular necrosis, rather than acantholysis [60,61,64].

3.4. Other than the skin, which organ systems may be involved in SJS/TEN?

SJS/TEN frequently affects multiple organ systems. The eyes are involved in 60–100% of cases, with manifestations including conjunctivitis, conjunctival and corneal erosions, conjunctival ulcers, pseudomembrane formation, and anterior uveitis. Consultation with an ophthalmologic specialist is recommended within 1 to 2 days of diagnosis [3,23,25,65,66]. The gastrointestinal tract is commonly affected through mucosal erosions, hemorrhagic crusting, and pseudomembrane formation of the oral cavity (up to 90% of cases). Additionally, mucosal erosions can affect the nasopharynx (50% of cases) and laryngopharynx (30% of cases) [3,22]. Erosions of the epithelial lining of the esophagus and intestines can also occur [1,67]. In one retrospective review of patients admitted with SJS/TEN who underwent endoscopy during their hospitalization, 11 of 20 (55%) were diagnosed with esophageal lesions [67]. Esophageal stricture is a known complication of SJS/TEN [1]. Epithelial erosions can affect the urethra and genitals in 60–70% of cases, which can lead to urethral stricture, vaginal adenosis, and adhesions [1,26,27]. The lungs can be affected through bronchial and alveolar erosions, which occur in approximately 10% of cases [28,34]. Patients may develop bronchiolitis obliterans as a complication [1]. SJS/TEN is associated with renal injury due to pre-renal azotemia and/or acute tubular necrosis [1]. Finally, SJS/TEN is associated with liver injury, suspected to also be due to mucosal injury, though there are reports of hepatocellular necrosis and ischemic hepatitis [1].

3.5. What are the clues on laboratory testing for SJS/TEN?

There is minimal role for laboratory testing to confirm the diagnosis of SJS/TEN in the ED. Anemia, leukopenia, neutropenia, and elevated creatinine may occur in acute SJS/TEN, although are nonspecific for the diagnosis [3,18,68]. Additionally, serum lactate dehydrogenase level can be elevated, although this is also nonspecific [69].

Several biomarkers have been identified as being elevated in the serum of patients with SJS/TEN, including Fas ligand, granzyme B, soluble CD40 ligand, granulysin, high mobility group protein B1, RIPK3, galectin 7, CCR-27, and IL-15; however, these tests are not available in the ED setting and will not assist the emergency clinician [15,69].

Despite this, laboratory studies can assist the emergency clinician in risk stratification. The SCORTEN score is based on seven clinical and laboratory criteria and has been validated in determining prognosis, including mortality, in both adults and children (Table 3) [3,14,[70], [71], [72], [73], [74]].

Table 4. The SCORTEN score.

Prognostic Factors | |

-Age > 40-Heart rate > 120 per minute-Known malignancy-Initial TBSA >10%-Serum BUN >28 mg/dL-Serum bicarbonate <20 mEq/L-Serum glucose >252 mg/dL | |

Prognostic Factors Present | Predicted Mortality During Acute SJS/TEN |

0 or 1 | 3% |

2 | 12% |

3 | 35% |

4 | 58% |

5 or more | 90% |

3.6. What are pearls and potential pitfalls in the management of SJS/TEN in the ED?

The most important step in the management of SJS/TEN early identification of the causative agent. Immediate cessation of the causative agent significantly improves survival [39]. As discussed, the ALDEN can be useful in determining the causative agent, but up to 30% of cases will not be associated with a specific trigger such as a medication or recent infection. In the setting of a mucocutaneous eruption suggestive of SJS/TEN, the diagnosis should not be excluded due to the failure to identify a trigger.

In SJS/TEN, superimposed infection is common, with sepsis the leading cause of death. Sepsis should be considered in any patient presenting in critical condition or with abnormal vital signs in conjunction with a suggestive mucocutaneous eruption [15,37]. Antibiotic therapy should include coverage for methicillin-resistant and sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Enterobacteriaceae subspecies, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, though Staphylococcus aureus strains are more common in acute SJS/TEN while the latter are more common during hospitalization [2,3,6,16,37,38]. Accordingly, appropriate regimens include vancomycin or linezolid with cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam, meropenem, amikacin, or aztreonam. If there is no evidence of superimposed infection, prophylactic antimicrobials are not recommended as their administration could increase the risk of the future development of a multidrug resistant infection [16,37,38].

Additionally, patients with SJS/TEN are at high risk of hypovolemia due to mucocutaneous breakdown. Boluses of crystalloid may be necessary to achieve euvolemia. Following resuscitation to euvolemia, a maintenance infusion of crystalloid should be started. The quantity of fluid replacement required in the first 24 h in patients with SJS/TEN was estimated in one retrospective study to be 2.2 mL per kg per percent TBSA detached, though it is recommended to adjust the hourly infusion rate as needed to maintain a urine output of 0.5–1 mL/kg/h [75,76]. If patients remain hypotensive after fluid resuscitation, vasopressors such as norepinephrine should be initiated.

SJS/TEN can cause acute respiratory compromise requiring airway management. Indications for intubation in the ED include inability to protect the airway and respiratory failure, which can occur secondary to mucosal injury, pneumonia, and other pulmonary sequelae [34]. In the setting of hypoxemia, bronchial mucosal injury should be suspected even if the chest radiograph is unremarkable [14]. An early intubation strategy can be considered in patients with signs of respiratory involvement, such as hypoxemia, hemoptysis, expectoration of bronchial casts, and respiratory hypersecretion. Intubation can also be pursued for refractory severe pain, although clinicians must balance this indication against the risks of the procedure, such as the development of ventilator associated pneumonia, barotrauma, and further injury to the pharyngeal and respiratory mucosa [34]. During the intubation procedure, a smaller diameter endotracheal tube may be required due to laryngeal edema. The ventilation strategy should mirror that of acute respiratory distress syndrome, which includes a tidal volume of 6 mL/kg of ideal body weight, a positive end-expiratory pressure sufficient to avoid atelectasis, maintaining plateau pressures <30 cm H2O, and permissive hypercapnia [34].

Cutaneous wounds can be gently cleansed with sterile water or dilute chlorhexidine and covered with sterile non-adherent gauze. If available, silver-impregnated dressings may also be used [32,33]. Blistering and bullous areas should not be aggressively debrided or ruptured [32]. The emergency clinician may apply preservative-free artificial tears or sterile saline rinses to ocular wounds [32]. Other aspects of supportive care in patients with SJS/TEN include the administration of analgesics, antiemetics, and correction of any electrolyte abnormalities [2,3,15,38].

Several systemic therapies have been postulated to reduce mortality from SJS/TEN, including cyclosporine, etanercept, infliximab, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), plasmapheresis, and parenteral corticosteroids [14]. While some of these medications, including cyclosporine, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors, and IVIG have shown some promise in small trials, the body of evidence is mixed, and there is a paucity of large, randomized, placebo-controlled studies on the topic [14,15,20,33,[77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87]]. Therefore, it is not recommended that these treatments be empirically initiated by the emergency clinician without consultation with the admitting physician.

Patients with suspected SJS/TEN require admission at a hospital with a burn unit [14,32]. The treatment of SJS/TEN requires a multidisciplinary approach, with consultations with specialists in critical care, dermatology, burn surgery, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, pulmonology, gastroenterology, nephrology, urology, gynecology, psychiatry, wound care, and nutrition often necessary [2,14,32,88]. Therefore, it is crucial for the emergency clinician to arrange for the patient to be admitted to a facility with these capabilities in an expeditious fashion, as delay is associated with increased mortality [89].

Table 5 provides pearls and pitfalls concerning the evaluation and management of SJS/TEN.

Table 5. Summary of pearls and pitfals in the management of SJS/TEN.

Cutaneous findings suspicious for SJS/TEN include ill-defined painful erythema which progresses into dusky, purpuric, and atypical targetoid macules. Involvement of at least one mucous membrane is typical and up to 80% of cases involve multiple mucous membranes.

Any patient presenting with a suspicious mucocutaneous eruption should be treated as a case of SJS/TEN until proven otherwise through histopathologic testing. Such patients should be admitted to a hospital with specific expertise in the condition, and broad specialist availability to manage potential complications, including experts in burn/wound care, dermatology, critical care, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, pulmonology, gastroenterology, nephrology, urology, and gynecology. SCORTEN can assist in the prediction of mortality from the disease.

Sepsis is the leading cause of death in patients with SJS/TEN; the emergency clinician must have a low threshold to initiate broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. However, prophylactic antibiotics in the absence of infection are not advised. Other organ systems commonly affected include the eyes, respiratory tract and lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary system.

Patients with SJS/TEN are at risk for hypovolemia. Boluses of balanced crystalloids may be used to achieve euvolemia, with subsequent transition to a maintenance infusion to maintain a urine output of 0.5 to 1 mL/kg/h.

Consider intubation in patients with extensive oral, pharyngeal, and/or respiratory involvement.

Although most cases of SJS/TEN are associated with a specific exposure to a medication, such as aromatic anti-epileptics and sulfonamide antimicrobials, or infections, such as

Mycoplasma pneumonia

and the Herpes simplex virus in as many as 30% of cases there will be no identifiable trigger; the absence of an obvious exposure on history does not preclude SJS/TEN in a patient presenting with a characteristic mucocutaneous eruption. The ALDEN can assist in the identification of causative medications.

In the ED, cutaneous wounds can be cleansed with sterile water or dilute chlorhexidine and then covered with sterile, non-adherent gauze. Silver-impregnated dressings may also be used. Blistering areas should not be aggressively debrided or intentionally ruptured.

There are other dermatologic conditions associated with sloughing of skin, including PV and SSSS. However, in PV, normal appearing skin can slough with the Nikolsky test, which is not the case in SJS/TEN; SSSS can be clinically distinguished from SJS/TEN as the mucous membranes are typically spared.

Although there are immunomodulating therapies which may decrease mortality from SJS/TEN, controversy exists regarding their efficacies. The decision to initiate such therapies should be deferred to the admitting physician.

4. Conclusions

SJS/TEN is a continuum of a rare, delayed hypersensitivity reaction causing de-epithelialization of the skin and mucous membranes and is associated with a high risk of morbidity and mortality. Most cases are triggered by recent exposure to medications, although some cases are associated with a recent infection or have no apparent trigger. SJS/TEN should be considered in any patient presenting with a blistering mucocutaneous eruption. Laboratory and radiographic studies commonly available in the ED are nonspecific for confirming the diagnosis, though they can assist in identifying complications such as infection, which is the most common cause of death in patients with SJS/TEN. ED management should include identification and stabilization of any threats to the airway and breathing, provision of fluid resuscitation, and treatment of any superimposed infections with broad spectrum antibiotic therapy. Although there are several immunomodulating medications which have shown promise in decreasing mortality from SJS/TEN, controversy exists regarding their efficacies. All patients with suspected SJS/TEN should be admitted to a burn center, where patients will receive care from a multidisciplinary team.

.png&blockId=a4d3b3b4-055b-4aac-8427-dd932bd026b1)